Remarks from former Ch'ing-shih wen-t'i co-editor Susan Naquin, Professor Emerita of History and East Asian Studies, Princeton University, at the Association for Asian Studies meeting in March 2015 on the journal's history.

The Society for Qing Studies was first embodied in a journal called “Ch’ing-shih wen-t’i 清史問題,” “Problems in Qing History.” During the last fifty years, the journal has changed its name, but the Society has not. I would like to use my time today to talk about this idea of “Qing Studies,” its past and its future.

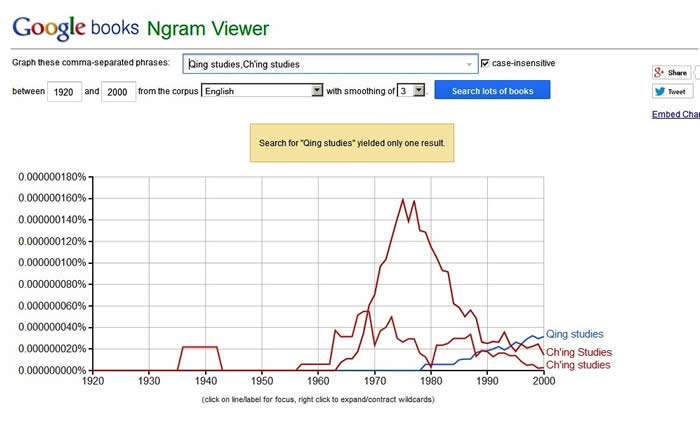

The idea of “Something Studies” may seem natural to us today, because we now have all kinds of journals in the China field with this kind of name. But they all were started after 1965. The phrase “Qing Studies” was apparently quite new. Using Google’s ngram, I could not find any uses of the phrase prior to 1965. Thereafter, the phrase rises in usage.

So where did this idea come from? There were precedents in Europe: earlier journals of Jewish Studies, British Studies (1961), Development Studies (1964) . And some parallel “Societies for X Studies.” But I can’t find many before our “Qing Studies” that were focused on one era. Byzantine Studies, 1974. Of course, there had long been the concept of “Studies on Something,” Études sur … , Studien zur .. . Not to mention shemma shemma yanjiu 研究, nani-nani kenkyū. So “studies” was hardly a strange idea in the East Asian field.

But there was another precedent closer to home, indeed, our home right at this moment: the Association for Asian Studies. It began in 1948 , as some of you know, as the “Far Eastern Association,” and its journal was the Far Eastern Quarterly. It was not renamed until 1956, when “Far Eastern” became “Asian” and “Studies” was added. That was only nine years before the Society for Qing Studies.

Every family has its ambiguous ancestors, and so does the “Asian Studies” family to which we all in this room belong. In 1950, several major U.S. foundations, especially the Ford Foundation, decided that what it called “Area Studies” needed major funding to produce scholarly knowledge of the new post-war world, including language training and what some would think of as Intelligence Necessary to National Security. And so the Ford Foundation began supporting the creation of such Area Studies programs in American universities. The centers thus created, with their libraries and publishing activities, produced the first generations of scholars in Chinese and Japanese Studies. Then, in 1958, in the wake of sputnik, the U.S. Government joined in, and began funding what were then called “Title VI Language and Area Studies Programs.” (NASA and DARPA were created at the same time, I might add.) For my generation, Title VI was the funding that made possible the study of Chinese and Japanese in graduate school.

There was an accompanying intellectual argument for “Area Studies” as a scholarly endeavor based on convictions about the seemingly intrinsic value of interdisciplinarity. Bringing together scholars who worked on both the past and the present, who would not be divided along “narrow disciplinary” lines, also had the advantage of keeping the increasingly influential, policy-oriented social scientists in touch with those who knew about the history, and it allowed “less relevant” scholarship to benefit from the largess that was pouring into these fields. And so, from this beginning, developed the graduate programs in “Chinese Studies,” “East Asian Studies,” etc. in which many of us were or are being trained.

So in the 1960s and 1970s, Asian Studies, with it Chinese Studies, Japanese Studies, and so forth, had their own strongly American shape, institutionally and intellectually, one that may be quite distinct from counterparts in other parts of the world. And this American context was certainly familiar to the scholars—themselves from precisely these funded universities—who cooked up the name “Society for Qing Studies.”

The idea of Qing Studies, even though it did not become part of the journal name when Ch’ing-shih wen-t’i became Late Imperial China, seemed to have a certain appeal. The Journal of Japanese Studies was created in 1974. Ming Studies in 1975. The Newsletter of Nan-bei-chao Studies in 1977. The Bulletin of Song-Yuan Studies in 1978. Tang Studies 1982. And so forth. I suspect that this usage feels rather comfortable to most of us.

And it turned out to be a fortunate phrase, especially the Qing part, when scholars began to take seriously the Manchu dimensions of this dynasty. And the “New Qing history” could point to the ways that this dynasty might be seen as distinct from its so-called Chinese predecessors. The idea of Qing studies thus continued to overlapp nicely with this kind of Qing history.

The status of Qing Studies may have also been enhanced by the more general ascendance of the idea of “cultural studies.” This phrase seems to have had its origins in Britain, and it took off in the 1970s. The ngram curve for the appearance this phrase in books has a sharp rise like a cobra about to strike! Cultural studies, as a concept, gave a different kind of legitimacy to the word “studies.” It conveyed the idea that “studies” were not merely 1) a deep and detailed investigation of a subject (Studies on the Population of China), and they were not necessarily 2) focused on a certain nation or language (the series “Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies), but, rather, they were 3) a theoretically informed approach to the study of human beings, past or present. I don’t mean to suggest that fields such as Qing Studies took on this kind of theoretical seriousness, most did not. But I do think that the idea of “Something Studies” was enhanced by the association.

Certainly, “Qing Studies” as an idea and as a field of activity is very much alive and well today. Uses of the phrase in Google Books show a steadily rising line since about 1980. The phrase is familiar, and common in English. Neutral. Even harmless. And here we are, the Society for Qing Studies. For myself, perhaps because of my involvement with the journal, the phrase as been a kind of arc over my whole career. Very nice!

But, of course, as we all know, today’s harmless and “natural” concepts will certainly be ridiculed and rejected by scholars of the future. “Qing Studies” as a phrase will not last, I can assure you. Later scholars will marvel that we could have embraced it so readily, accepted it so easily. For, of course, it is when you are most comfortable with a concept that you are most blind to its problems. Although I may be too much inside to really see where we are going, I can tell even now that “Qing Studies” is not without its “issues.”

I don’t think a change will come from any conscious rediscovery of its Cold War origins, although that may catch up with us eventually. The funding situation that created Asian Studies centers and programs has greatly changed, the well-invested money of the 1950s and 1960s is still there but not necessarily directed at the same purposes. Chinese and Japanese programs, once joined, have separated, but there are still Centers for Chinese Studies at Berkeley, Michigan, UCLA, Harvard, and many foreign universities. But I am not so sure that interdisciplinarity has created common intellectual ground. “Interdisciplinary” is a word that is thrown around to create alliances, and today we are more likely to have separate fiefdoms rather than active intellectual communities. And, of course, multi-disciplinarity has always worked as much against dialogue as for it.

What does this phrase, “Qing Studies,” do for us? It does provide an arena for shared interests: First, Geographic—the Qing empire. Second, Temporal: the Qing dynasty. Certainly, our knowledge of this time and place has expanded and deepened enormously in the last fifty years. Impressively. And there may be more of a shared intellectual conversation across disciplines than in the days of Ch’ing-shih wen-t’i. At the same time, it seems rather obvious to me that people are already chafing at these geographic and temporal limits. Calling the journal Late Imperial China was, I believe, a deliberate recognition that 1644 and 1911 are arbitrary boundaries, best treated loosely.

And yet, Late Imperial CHINA does not acknowledge the problem that many of us now have with the word “China.” It too used to seem natural and harmless. I now see it as nationalist propaganda about the past and a word to be avoided entirely in writing about the Qing period; and I am hardly alone in this. Moreover, as you all well know, recent experiences with globalization have made us all much more conscious about trans-national connections and issues, and many scholars are now standing on the edges of the Qing empire and looking in more than one direction.

People seem to feel comfortable saying that they work in Cultural Studies, but I don’t think there are many of us who would relinquish our disciplines and say, “I do Qing Studies,” instead of Qing literature, intellectual history, art, etc. Indeed I’m not sure how many people in this room feel that our work is limited to “the Qing” either as a time or a place. There may be a kind of flimsiness to the concept that will make it vulnerable and easy to reject as time goes by. So, our intellectual common ground may be shrinking, even as the number of publications grows and grows. At the same time, although the academic institutions that created “Chinese Studies” are more and more subdivided, I don’t expect to see a center for Qing Studies any time soon. And would I want one?

So if “Qing Studies” has any vigorous institutions to keep it going, would they be the Journal and the Society? The journal appears twice a year and announces that it is “for scholars of China’s Ming and Qing dynasties.” It does not use the phrase “Qing Studies.” And it is explicitly colonizing the Ming. The Society, which scarcely ever met in the first thirty or forty years, now manifests itself—with somewhat greater regularity—at the AAS meetings, once a year. Our counterparts in Tang Studies and Ming Studies have been much more energetic for a much longer time. And there is the relatively recent website. There, it declares that “We hope to provide a gathering place full of resources for scholars interested in the Qing Dynasty as well as information for those interested in publishing in our journal, Late Imperial China.” It invites work in a “in a range of disciplines and representing diverse perspectives on the Ming and Qing periods.“ And it offers a Listserv.

“Qing Studies” as a label is not, however, the same as Qing studies as a field of research. Are problems with the name indicative of problems with the work? You all may be better equipped than I am to tell whether the website, the journal, and the society can provide sufficient intellectual or institutional momentum to keep the study of the Qing meaningful, with or without the name. For myself, I am not sure if the points I have mentioned in this talk are evidence for the strength of Qing Studies or for its weaknesses. Perhaps both.

When I started writing these remarks, I intended to be celebratory, but I have ended up sounding like Cassandra. So let me conclude by saying that—as much as I have enjoyed my career, sheltered within the commodious phrase, “Qing Studies”—I do feel sure that as a label, its days are numbered. My advice for you all is: Look Ahead. Be Ready.